Holocaust Remembrance, a Houston Childhood, and Texas History

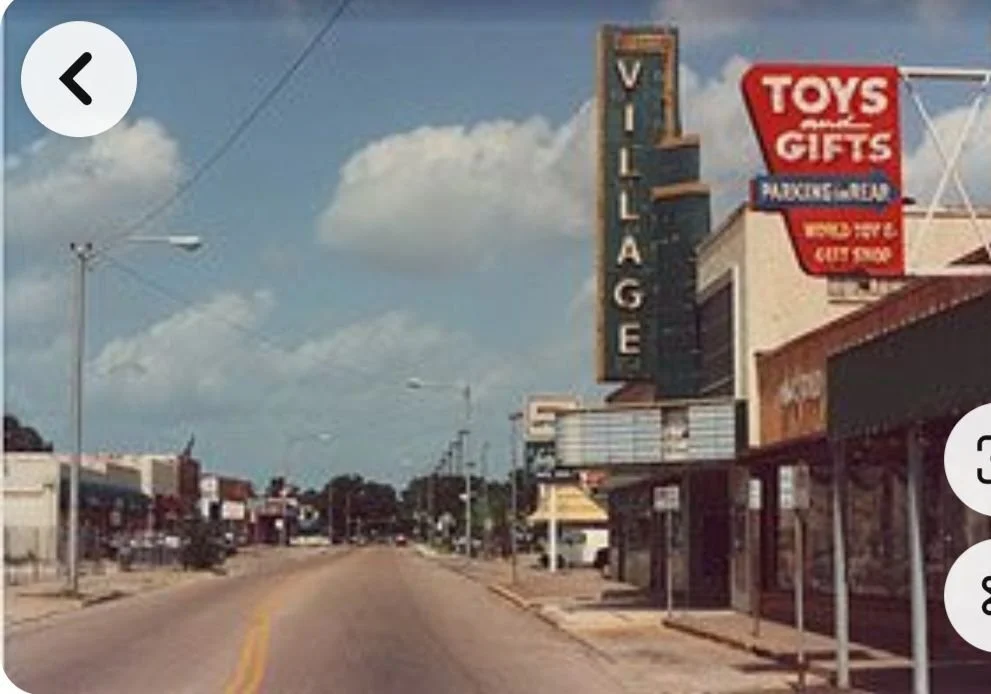

Rice Village, undated [1980s?]. Photo by Peter Bloch

On the occasion of Holocaust Remembrance Day in 2026, I am reproducing a talk I gave last year at Holocaust Museum Houston, to open their hosting of the traveling version of the exhibit “Life and Death on the Border.”

I grew up a few miles from here, on the edge of the Rice Village. These days, the village is pretty upscale, but it wasn’t always so. Maybe I’m not the only person in this room who remembers modest, funky stores like the old 5 and Dime, the Blue Hand, and two very seedy pornographic theatres. And then there was World Toy and Gift. I used to go to that toy store all the time, buying board games, miniature soldiers, and Dungeons and Dragons modules. It was a magical place, presided over by Rose Behar and Adelaide Friedman, two elderly women who were not to be messed with. One day – I must have been about 10 – Mrs. Behar was counting out my change, when her sleeve rode up her arm and I saw a series of numbers tattooed on it.

And that was how I learned about the Holocaust. I remember my mother explaining to me in the car ride home, calmly but . . . unsparingly, that decades before, when Mrs. Behar and Mrs. Friedman were young women, the German government had herded people, mostly Jewish, into camps and killed millions of them in gas chambers and burned their remains.

Crazy!

This was very difficult to understand: I was still young, grew up in a loving family, had no experience of violence, didn’t know what Germany was. I don’t think that I really knew what a Jew was – maybe something to do with the bible that my mother read to us at bedtime?

Of course I learned more in the following teenage years: I came to know all of the racial slurs of American life, witnessed and experienced violence, had Jewish classmates, friends, teammates, colleagues, and later, in-laws. I learned about the holocaust in school and especially from watching movies. There I also learned about Germans, with their high boots, militaristic bearing, and harsh, guttural language. Yet though I encountered the Shoah in one of the familiar places of my Houston childhood, it remained foreign and distant: something done thousands of miles away to a people I did not belong to, perpetrated by people I had nothing in common with.

The subject of the exhibit we are here to discuss is much closer to home, especially for those of us deeply rooted in Texas. “Life and Death on the Border” tells the story of the Mexican community of what is now South Texas, which became part of the United States by conquest in 1848 with the conclusion of our war with Mexico. It describes how they made a home in this beautiful but harsh region, and how they survived an enormous wave of violence that swept over them in the 1910s. It presents visitors with opportunities to learn about perpetrators of the violence, the people they victimized, how dehumanizing and fear-mongering rhetoric created a justification for mass murder, and about the reverberations of violence across the generations, as my colleague Dr. Carmona will shortly discuss.

The middle portion of the exhibit, really the “death” in “Life and Death,” takes an unflinching look at one of the worst sustained episodes of racial violence in the history of the United States. Hundreds if not thousands died at the hands of their neighbors, vigilante mobs, local law enforcement, US soldiers, and the Texas Rangers. They were shot along roadsides and in fields, huddled together and gunned down, tortured and murdered in front of their families, hanged from trees, decapitated, tied to logs and set loose in the Rio Grande; their bodies were sometimes left in the open for months, other times burned en masse or defiled. The mourning families of some victims had no idea who the murderers were and called for investigations. Other families knew exactly who killed their fathers, uncles, brothers, sons and daughters, and they endured knowing that some of them held high offices and positions of social prominence in the years and decades to come.

We are still learning about the full dimensions of this violence. Last year, one of our colleagues unearthed a 2015 letter from a former scoutmaster describing how his scout troup unearthed quote “human bones from these bandits” while camping in McAllen city limits. The site closely matches description of a mass murder site from the fall of 1915, and we are investigating.

Rose Behar, in her public statements at least, had nothing but good things to say about the United States. She found greater economic opportunity here, and a less rigid class system than in Bulgaria, where she spent most of her childhood. In her life, if not ours, she didn’t have to point out that there were few fascists here, and that they lived far from the corridors of power. Behar had a powerful presence; to be honest, like a lot of the kids who patronized World Toy and Gift, I was scared of her. When a family friend had her store robbed at gunpoint, Behar told her “Don’t be afraid. Never be afraid. It will cripple you.”

It’s no disrespect to Behar to note that others had very different experiences of integration into American life. Like all widespread state-sanctioned racial violence, the killings of the 1910s brought enduring consequences. Many ethnic-Mexican families abandoned their ranches and farms, trading economic independence for the exploitation of working as wage laborers at the bottom rung of the economy. Some moved to nearby towns, cities farther away, or to Mexico; many joined the ranks of the migrant agricultural workforce that toiled in Texas cotton fields, picked blueberries and sugar beets in Michigan, or labored in factories in Detroit or Chicago. “Mexicans are condemned to be the Jews of the American continent,” wrote one South Texas newspaper in these years, “to an eternal wandering, first from North to South, and now from South to North.” Laws and informal practices modeled on the suppression of Black people under Jim Crow excluded most Mexican-descent people from voting rights and service on juries, and confined them to segregated neighborhoods and schools.

I learned about this border violence more than a decade after my encounter in World Toy and Gift, while living in New England in my second year of graduate school. Unlike the crimes of the Nazis, this episode has everything to do with Texas. It was perpetrated by people with names like mine, who looked like me, who talked like my parents. And as the exhibit shows, the Texas Rangers, one of our state’s most iconic institutions, celebrated in some of my favorite childhood movies and TV shows, played an instrumental role in the violence. Also unlike the Holocaust, the events described in the exhibit are little known and rarely commemorated, although that has begun to change in recent years. My own interest in these events, which led me to write my first book in 2003 and help establish Refusing to Forget in 2014, came from the shock at my own ignorance: how could I know so much about US history but not know about such consequential events that took place in my own state?

Since I am juxtaposing the Holocaust with this chapter of Texas history, it is important to acknowledge that thinking about other events in the context of the Holocaust, and especially drawing parallels to it, is a tricky business. There is very little in human history analogous to the industrial mass murder conducted in central and eastern Europe in the 1940s. To describe a single massacre as a holocaust, or call anybody you don’t like a Nazi, demonstrates sloppiness and risks conveying disrespect for the victims of the Shoah.

And yet at the same, the memory of the Holocaust, and institutions like this one, are useless if we don’t compare, if we don’t take what we learn about the Holocaust and anti-semitism, and use it to understand other times and places and peoples. It will never again be 1941 in Germany, Poland, or anywhere else. We cannot learn anything from history if we do not compare. Instead of walling off the Holocaust from the rest of human experience, institutions like the Illinois Holocaust Museum near my current home, use it as a window from which to observe other episodes and better understand them.

As a professional historian and somebody who tries to be a good citizen, I think of the Holocaust as a perpetual reminder of where racism, fear, nationalism, and obedience to authority can lead. As somebody who has spent the last two decades trying raise awareness of our nation’s history of anti-Mexican violence, I have found the reckoning with the memory of the Holocaust in the Jewish diaspora and in Germany alike, to be an example and an inspiration. As an adult who has lived and taught in Germany, I have become very familiar with the most terrifying thing about Germans: that they are pretty much like everybody else, including those of us in this room.

I have also seen what it is like to reckon with your own history and your own nation’s crimes. In Germany, as everybody here may know, school children learn a great deal about the Holocaust: they visit the site of death camps and learn about the rise of fascism at every stage of their education. Stolperstein, or stepping stones, list the names, birthdates, and fates of Jews and others persecuted by the Nazi regime, weaving this history into the fabric of daily life. If you are training to be a doctor, you learn about the misuse of medical science, and if you are studying to be police officer, you learn a great deal about the role of police in the persecution of Germany’s Jews, and so on. The universities I’ve visited have memorials in central places that honestly tell the story of the dismissal of Jewish, socialist, and other faculty, and their institutions’ wider complicity with the Nazi regime and its many crimes. There are no streets named after Nazi leaders or even ordinary soldiers, and no museums extoll the sacrifices of the millions who fought for Hitler’s regime.

One of the key episodes in postwar Germany’s reckoning with its past was a museum exhibit on the Germany Army that was first displayed in Hamburg in 1995 and then across the country. It made the case that ordinary German soldiers – whose ranks were drawn from virtually every family – participated in the violence inflicted on Jews, Roma, Sinti, and others. It was controversial and provoked great anger in some quarters, precisely because every German had a relative in the army, whether that person wanted to be or not. But the exhibit cemented the strong consensus that German society as a whole, not just a small group of leaders, perpetrated the Holocaust and allowed it to happen, and thus that all Germans share in the responsibility of atoning for it and ensuring that nothing like it ever happens again.

The exhibit that we are here to open has hardly had such an impact, but I hope you’ll see the parallel intent as you walk through it. And I want to describe some of the similar opposition that we have faced, even from constituencies within this museum’s community.

Who here has been to the Texas Ranger Museum and Hall of Fame in Waco? The museum, supported by public funds, presents the Rangers as heroic police force that helped to create modern Texas. There is little mention of the events described in Life and Death on the Border, although in recent years after pressure from Refusing to Forget, they have listed the names of the victims of the 1918 Porvenir Massacre, described in the exhibit. In 2023, the Rangers celebrated their bicentennial, and despite our urging, continued to refuse to confront their role in the violence profiled in this exhibit, or in other horrific episodes. Russell Molina, a prominent citizen of Houston – you may know his family’s restaurants – with close family ties to the first Hispanic head of the Rangers, headed up the bicentennial campaign.

Molina was also on the board of Holocaust Museum Houston, at least as of several years ago, and I gather did everything he could to keep the exhibit from coming here. One staff member, since departed for other employment, told us that Molina warned him that quote “if you bring this exhibit here I will make sure that everybody in Houston knows how full of shit Refusing to Forget is.”

Here we are.

[if he’s in attendance (he was not): Russell, thanks for coming. I hope that you’ll walk through the exhibit and learn something from it. We’re here tonight, tomorrow we’re at Baylor, also opening the exhibit there, just a stone’s throw from the Ranger Hall of Fame; we’re all over the state. Our books and articles are assigned in courses across the country, and every month thousands of people read the information on our website, refusingtoforget.org. We’re not going away]

A set of events involving the Rangers not far from here in the late 1930s conveys how badly our institutions have failed to tell us the truth about our own history. In 1937, Bob White, a black farm laborer, was arrested 85 miles north of here and charged with raping Ruby Cochran, his white employer’s wife. There was no physical evidence to support the charge. White was held in the local jail, and soon Texas Rangers Maro Williamson and Edward Davenport arrived. Each night for the better part of a week they removed him from the jail, chained him to a tree, and beat him. White broke under the pressure in the midst of a 4 hour torture session, confessed, and was quickly convicted and sentenced to death. The Houston NAACP hired a lawyer and convinced a Texas appeals court to throw out the conviction as coerced. They took it all the way to the U.S. supreme court, which threw out his conviction as a violation of the 14th amendment’s guarantee of due process, in an important predecessor to the Brown v. Board decision that came 14 years later.

This precedent didn’t do Mr. White much good. He was again put on trial. Ruby Cochran’s husband, fearing that the supreme court’s instructions to toss out his confession would result in his exoneration, walked into the courtroom where White sat chained in a chair. This was in Conroe, Texas, 43 miles to our north. Cochran took out his gun and shot him in the head, right in front of the judge and jury. The next week he was acquitted and walked free. As was the case in the state violence described in this exhibit, White’s mother and wife were so afraid for their safety that they could not bring themselves to claim his body. The county buried him in a pauper’s field, where to the best of knowledge, he still lies in an unmarked grave.

This was June of 1941. Within months, several hundred men from Montgomery and Walker counties, where Bob White lived and died, joined the US army, black men as well as white, making their contributions in the war against fascism that would liberate Rose Behar from a Bulgarian concentration camp and eventually bring her to Houston and into my life.

For the last 20 years, I’ve regularly visited the Ranger Hall of Fame and museum in person and online. I have yet to see even a mention of this case, one of only two times that the conduct of the Ranger force has been adjudicated by the Supreme Court. That willful refusal to deal with history honestly, the moral cowardice of Russell Molina and his colleagues, is what this exhibit is meant to counter, and it’s why we named ourselves Refusing to Forget.

And so this exhibit is meant to tell a cautionary tale, very much in keeping with what I take to be the mission of this museum. It’s not a flattering story about American and Texan institutions. Unfortunately, it’s more relevant now than ever, as we enter a time when a charismatic leader again demonizes large swathes of the population, routinely incites violence, promises to take us back to a supposed golden age, asserts that he is above the law, and pardons the people he incited to overthrow the transition of power to his democratically elected successor; and as we again slam our doors shut in the face of people fleeing oppression, just as we did in the 1930s, and build camps to hold thousands out of public view and where the normal protections of the law do not apply. Sometimes the danger comes from strangers, like the German fascists in Hollywood films that Mrs. Behar’s story made me think of decades ago. Sometimes it comes from us.

Thank you for your attention.